The missing piece of the AI jigsaw - jobs

If we see an AI revolution, we'll need a jobs revolution too.

AI is not our first new tech rodeo. There’s a pattern. Essentially, you have the sceptics who question the fundamental economic impact of new technologies. They are generally right until they are suddenly wrong. Then there are the boosterists. They are generally right but usually over a much longer timeframe than they forecast - sometimes decades longer. So we have a very rough set of rules of thumb to navigate this debate.

When it comes to AI, we have Nobel prizewinner, Daron Acemoglu in the tradition of Robert Solow (“you can see the computer revolution everywhere but in the productivity statistics”) and Robert Gordon, in the sceptic camp. He sees likely productivity gains of less than 0.55% over ten years. In the booster camp we have the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change, for example, which sees public sector productivity gains of £200 billion over five years on the basis of current levels of AI capability. You can position a whole raft of perspectives along this sceptic-booster spectrum. My purpose here is not to adjudicate: it’s rather to ask, what if the boosterists are right?

The Government for its part is more towards the booster camp. And why on earth would it not be? Given sclerotic UK productivity, the unlikelihood of a comprehensive trade deal with the EU single market, the slowness of productivity gains from incremental innovation, and an economy structured around services over manufacturing, where else is rapid productivity growth likely to come from? This bet makes sense because in part there is so little else.

Let’s assume the booster characteristic of being right but over a much slower timeframe is right - but AI narrows that timeframe decisively. The Government believes this scenario is possible, even likely with the right plan in place. If this were to happen then there would certainly be a noticeable productivity effect. There would also be a jobs effect but the newly published AI Action Plan, concentrating as it does on growing the AI sector, is silent on some potentially significant aspects of the jobs effect - the wider labour market implications of rapid AI adoption.

Advanced nations have tended to experience a growth of jobs at the top and at the bottom of skills levels in recent decades - and a decline in the middle. The process, referred to by economists as polarisation, whilst visible in similar ways might have been driven by different factors in different countries. The US case seems to have been a story of technology, with information technology replacing routine, middle income jobs. In the UK, the changes seem to have been driven more by shifts in skill levels - most particularly the enormous growth in the number of graduates.

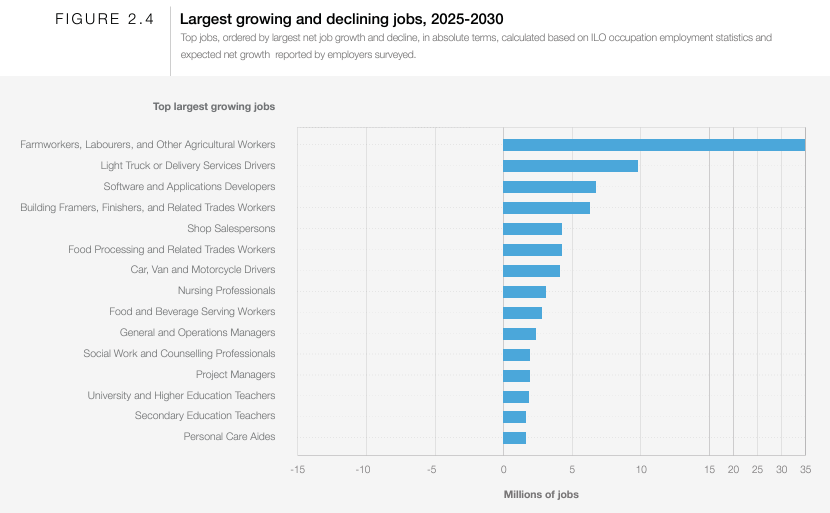

With rapid AI adoption, the booster scenario in other words, it seems entirely plausible that middle income occupations could be hit again. Imagine if we split the jobs market into three camps: “opportunity”, “resilience” and “at risk”. Opportunity is in fields such as we see in the “frontier economy” which requires complex, non-routine abstract skills. Think, well, creating AI applications as an example. We can see what this would look like in the latest World Economic Forum jobs report (again, I am taking these numbers as a scenario rather than a forecast)- these are the jobs with highest forecast net growth.

You can see that we have exactly what we’d expect to find there- lots of tech, finance, green specialist roles. But this is net growth - what about absolute growth? Here we see what I’ll term “resilient jobs”. These are large in number, non routine - such nursing or trades - and more located in the bottom half of the income distribution and have a high density in the labour-absorbing “everyday” and “care” economies.

And the “at risk” section of the labour market? These are more likely to be located in the middle of the earnings distribution but more “routine” in character. There are lots of roles containing the job category “clerk”.

And this is where the AI action plan comes in. We have to assume that the scenario is closer to the booster scenario and that the process of polarisation will be a consequence of that- and it will look more like US style tech-induced polarisation than UK-style expanding pool of graduates style polarisation (which tech would have helped reinforce anyhow). This has consequences for each of the three job categories:

Opportunity jobs. As the AI action plan aims to, we have to ensure we have adequate numbers to meet high level skills demand and we have to erect ladders to these opportunities both at entry level and mid-career.

Resilient jobs. The strategy here is one of improvement: to support job quality, ie wages, security and career progression. These jobs really cut through into standard of living and quality of life and if we ignore these features then we can anticipate some form of backlash and continuing chronic regional inequality.

At risk jobs. The key here is to enable adaptation. In our booster scenario there will be a lot of people who will need access to job transition and upskilling support. A lot of these workers would be in the public sector given there is a lot of “clerking” there.

The good news is that, should a AI-driven jobs revolution come, it won’t be a process like deindustrialisation. There won’t be entire local economies that are laid to waste such as when a steel plant or car factory closes. The advantage of having an economy weighted to services is that impacts are dispersed geographically, albeit with a different profile between places. A dispersed impact will also hide a lot of unnecessary harm. However, the benefits are not equally dispersed and, instead, concentrated on regions with high current productivity, most particularly London. This is a source of discontent and political volatility - a bad thing for consistent policy such as remaining part of a single market.

Previously, I explored the gap between aggregate growth and the experience of growth - see Trump and the Everyday Economy. And this is why a proactive work transition strategy is necessary in case of the AI booster scenario. To be honest, even if that’s not the scenario, a more proactive and coherent work transition system is necessary anyhow. And, by the way, in a transition economy, blocking investment in mid-career up- and re-skilling as would be the consequence of some recent proposals with respect to the apprenticeship system, is pretty much entirely the wrong direction of travel without significant new public funding (which, given fiscal constraints, is unlikely to arrive).

There are a lot of moving parts here. On employment rights, wages, skills, industrial policy, devolution, the AI action plan itself, there are many of the bases covered. However, there seems to be a big picture piece around the future of work that seems quite hazy through all of it. Given what we have seen in past phases of tech acceleration, we know that adaptation will be necessary. And adaptation to a changing future of work feels like a policy arena in need of acceleration.