The limits of growth-ism

The Government has reverted to the "standard model" of UK growth first seen in the mid 1980s. This time it must spread economic opportunity more widely and not ignore real environmental trade-offs.

There has been much discussion in the first few weeks of the year about the Government’s growth mission. The goal was clear but what was the strategy? And in the past fortnight that question has been answered decisively. The economic statecraft is now reasonably closely aligned to the default statecraft of the UK state - the “standard model” - since the 1980s: growth industries, foreign direct investment, and re-regulation.

In highlighting this policy mix, the intention is not to somehow label the strategy as “neo-liberal”. It’s rather to observe a pragmatic response to the UK as a service-based economy in a global market. For finance in the 1980s see life sciences and AI in 2025. For Japanese car manufacturers see global tech giants. And for the “big bang” see growth focused market policy over competition-centred innovation. The parallels are striking and the “standard model” seemingly hard-wired into the logic of the modern British state. We try other options - Brexit, levelling up, whatever the Liz Truss craziness was - before arriving right back here. Nice to see you again.

There are differences. We can’t take advantage of our position in a unifying and expanding single market as we could following the Single European Act 1986. Margaret Thatcher was far smarter than her Conservative successors when it came to European trade. This Labour Government is increasing some employer taxes and employment regulations, whereas the Thatcher Government was headed in the opposite direction. After falling from 1960s/70s highs, housebuilding stabilised before increasing prior to the early 1990s recession. This Government would love to see such an outcome.

So there are lots of parallels albeit with some noteworthy differences. The anomalies were actually the Conservative Governments of Theresa May, Boris Johnson and Liz Truss. Every other British Government since the mid-1980s has pursued broadly the same economic statecraft, now including this Government too- the “standard model”.

It is completely understandable why. The Autumn Budget was a politically bracing experience for the Chancellor. She was completely boxed into a corner politically and fiscally. She rightly changed fiscal rules and increased public investment which was astute. Nonetheless, I have no doubt that she never wants to be in that position again and so a pragmatic course on growth makes absolute sense from that point of view: increasing tax revenues make sharp political edges somewhat blunter. And British state default policy has served different administrations well in the main. And as argued previously on this blog, which was established to consider the connections between the frontier, everyday and care economies, focusing on the “frontier” is crucial and that is what this growth strategy does. It’s also incomplete and contains two big risks.

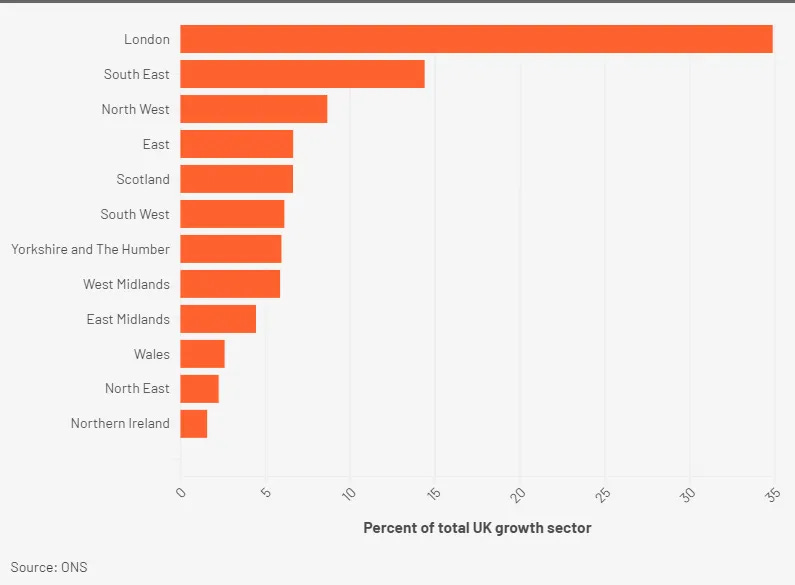

Whether you like it or not, a growth economy focused strategy ends up heavily focused on where national productivity is already high and that is London and the South East. Regeneration around Old Trafford won’t be enough to counter this dynamic. Here is the broad regional distribution of the “growth” economy from a previous blog, We’re going to need an even bigger bazooka.

We know that the “standard model” widens regional inequalities and we also know that over time this creates an increased state of political desolation and alienation. In fact, in the 2016 referendum this sense of anomie was one of contributory factors behind Brexit - the one thing that briefly disrupted the standard policy since the 1980s. The purpose here is to highlight the gaps in the policy from a viable statecraft perspective. And proposals for mega 500,000 population plus unitary councils in order to make efficiency gains on social services starts with neither political alienation or sustainable growth in mind.

And it is to sustainable growth we now turn. There is a linkage here with the 1980s too. In 1988, there was a speech given to the Royal Society by Margaret Thatcher. It is worth a read. It shows how far many on the right of politics have fallen for one thing. In it, from a free market perspective, Thatcher manages to combine belief in wealth creation with an awe of science balanced with an ethical outlook on our corrosion of the natural world. She says, some may be startled to hear:

“Stable prosperity can be achieved throughout the world provided the environment is nurtured and safeguarded.”

The construction is important: the environment is given first order status. A stable economy is dependent on nurturing and safeguarding the environment. We have no means of knowing what her policy follow-through might have been on Net Zero though she did explicitly reference her concerns that carbon emissions were destabilising the planetary equilibrium. Compare this to Rachel Reeve’s remarks yesterday:

“There is no trade-off between economic growth and net zero. Quite the opposite. Net zero is the industrial opportunity of the 21st century, and Britain must lead the way.”

“Green growth” or “green industrial strategy” has been embraced by progressives for a decade or so. It was always risky as a political narrative and we can see why here. The risk was always that we would shift from “there are innovation, growth and jobs opportunities that must be secured” in green transition to “there is no trade-off between the two”. And that’s where we have arrived and it is why the green growth narrative was always problematic. Whilst much of the discussion has been about Heathrow, that’s not the fundamental issue at stake. The issue is one of deep policy structures: if the logic of “no trade-off” governs economic decision making when the trade-offs, if not carefully managed, are immense then we will fall desperately short of achieving Net Zero by 2050 or anywhere close.

Climate emergency is like death and taxes. We simultaneously have full knowledge that it is approaching; indeed, it is here already. And yet we possess no means of avoiding it. There are only two rational strategies: fatalism or doing the best we can to mitigate it by enabling people and communities to adapt. When it comes to decarbonising- we owe it to ourselves and future generations to do what's possible - within the constraints of not just the environment, but the society and politics we inhabit. And we should do so in full in the knowledge that such action may not be sufficient.

Pretending that we have no agency, denying or delaying climate action are forms of fatalism ultimately. They pass on misery and enormous cost through a destablised financial system, conflict, physical and economic risk and ill-health to future generations. Correction: our older selves and our kids. Some have taken a de-growth perspective where we deliberately shrink our economic and resources footprint in response. This takes the trade-offs as read and then reverses. Such a strategy is a complete non-starter in the society and politics we inhabit. The likely rapid outcome would be political backlash and the whole Net Zero project being undermined.

Such political dynamics, and Net Zero is more a political and cultural challenge than a technological one, are expertly explored by Jens Beckert in How we Sold our Future. Pragmatically, we are where we are and we have to adapt accordingly. I find myself stuck somewhere between “Net Zero by 2050 is a necessary global and national mission and we have to be focused in its pursuit” and “we are probably going to fail and so we also need careful planning for adaptation.” The landing space is a politics that holds both ideas in place and prepares for both futures.

That is not a politics of “no trade-offs”. It is politics that explicitly recognises trade-offs and realises that every decision it takes that is not compatible with Net Zero by 2050 means loading further economic and social costs onto the relatively near future. We have to ask ourselves, would our future selves and generations prefer to have additional airport capacity (and we are unlikely to see the third runway until the late 2030s if at all) or a better chance of avoiding economic de-stabilisation?

Just today, the Court of Session in Edinburgh has ruled that oil licenses granted to mine the Rosebank and Jackdaw oil fields are illegal on account of not fully assessing downstream, ie scope 3, environmental costs of burning their output. The Climate Change Act as amended in 2019 commits the UK to meeting Net Zero by 2050 through a series of carbon budgets - and we are already beginning to fall short. It seems reasonable to expect that major new developments are at least plausibly in line with these goals.

An airport expansion that relies on some vague narrative about sustainable aviation fuel - as clearly discussed as ever by Hannah Ritchie here - wouldn’t seem to be consistent with our legal commitments nor would drilling for new oil. The point is not particularly the direct impacts themselves. It is the logic which when applied more widely, by the UK Government and every other Government in the world, would very likely lead to a massive overshoot on Net Zero.

So the trade offs are very real. It is striking that the Limits to Growth, a 1972 global best-seller which explored scenarios on macro features such as population, output, pollution and resource depletion, was broadly right to see natural limits to growth despite ferocious criticism over the years (not to say the models were accurate- just that they spotted something important). That thinking is visible in the Thatcher speech in 1988. We are almost four decades on. The trade-offs are becoming more acute if anything and unless we make more choices to prioritise the environment then those trade-offs become even more so.

The standard British model needs updating. One flurry of announcements is not the whole story so there is time and space to develop policy thinking further. But from here on in, more is needed on spreading growth out, not least geographically, but also ensuring that we give ourselves the best chance possible of getting to a Net Zero world within a quarter of a century. Yes, growth-ism does have limits.

It's a really thoughtful article, Anthony. Thanks for sharing it. Some great links to resources too that I'll follow up. It's almost like being at the RSA!