A new economic paradigm?

The Budget pointed in a radically different direction with the Chancellor judging the opportunities and risks well. A better growth paradigm will require further innovation across the board.

In a week when we have had a very significant fiscal event, a Budget that genuinely forged a different direction, it is worth taking a step back to consider where that pathway might be heading. Taken together with the draft industrial strategy published a couple of weeks ago and a variety of institutional innovations such as the creation of a National Wealth Fund and Great British Energy, a new British economic paradigm is beginning to emerge. How can it become more fully formed?

Getting crowded in here

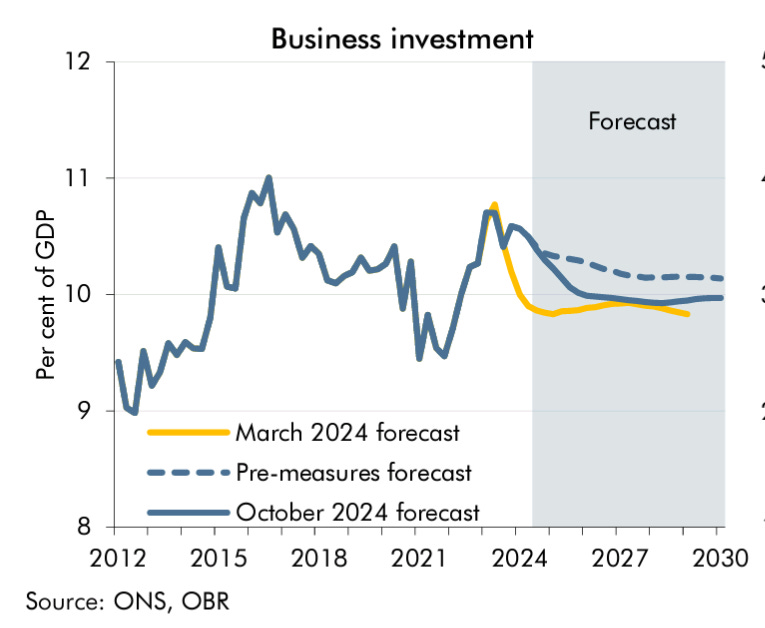

It is important to package any talk of a new paradigm with a large bundle of caveats. Gilt markets and the ratings agency, Moodys, are sounding a slightly cautious note post-Budget even if the IMF is more bullish. The scale of the investment either in terms of capital investment or investment in a number of areas of public service, notably health, education and justice, is significant and important but not yet transformative. The Office for Budget Responsibility is not convinced that the measures will crowd in private investment, in fact seeing the opposite as somewhat likely as shown in the graph below:

Indeed, if this is the outcome then we won’t be in a new paradigm. We will be in a slightly more indebted version of the current paradigm but with a faster pathway to net zero and marginally better hospitals, schools and prisons. There’s cause for greater optimism perhaps. With increased employer national insurance contributions beyond the smallest employers and higher national living wage rates, there is an incentive to invest in labour-saving technology and processes. Shifting regulation of planning should encourage investment in built assets. The National Wealth Fund and direct Government investments may more successfully crowd in wider investments in technology and energy. These are all possibilities that will bend the investment curve upwards.

This is all just the opening flurries of a very different approach to the economy - one that we haven’t seen in the UK for half a century. Of course, part of this is just the acceptance that the UK is an ageing, low productivity growth, post-Brexit economy and so has to face its higher tax fate. More broadly, the Government is trying to build a developmental state out of a regulatory state that has operated on the basis of market oversight and risk management. That involves thrusting the levers forward rather than just watching the dashboard and only intervening when there’s a red light.

A British developmental state?

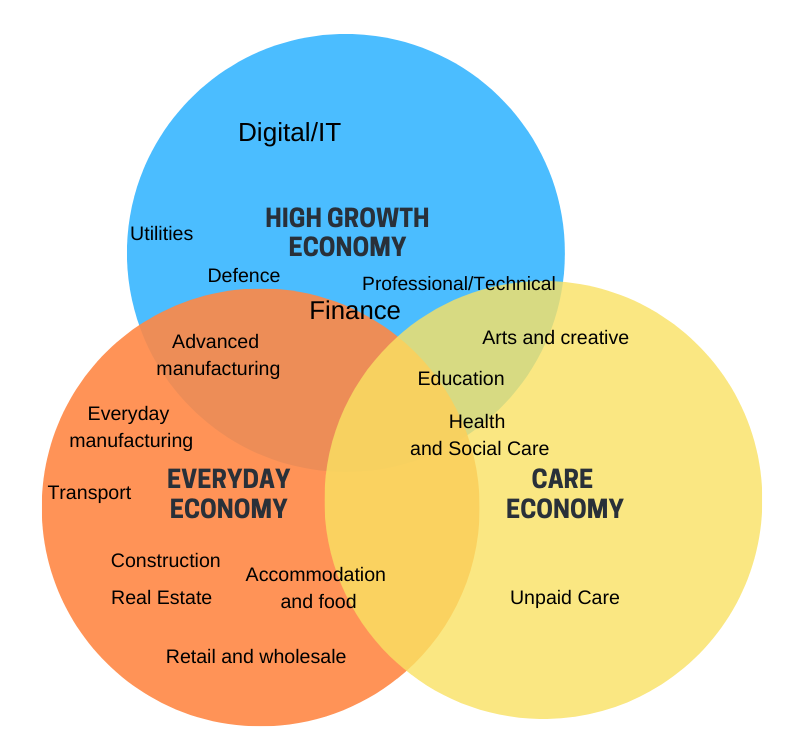

Developmental states or strategic investment states are pretty good at delivering catch-up growth for a period of time. David Marquand long bemoaned the ability of Britain to create its own developmental state akin to Japan, France, or Germany. We can add South Korea, China and indeed, perhaps surprisingly, the US to the list in the past few decades. There is plenty of catch-up physical and technological capital ready to be deployed with the right type of state support. So if you have a growth mission that’s a good place to start. And when you think about the “three economies” I have previously outlined we see significant growth-supporting interventions in this Budget in each:

Health, education and unpaid care (through improved carers’ income allowances) improve the care economy. Business rate exemptions and employer national insurance contributions contribute to small businesses in the everyday economy. And support for aerospace, green investment, and the car industry contribute to both the growth and the everyday economies.

The Resolution Foundation makes the point that too much of the support for business is centred on low growth, low productivity firms. The final industrial strategy and the spending review will have to consider how to incentivise better technological adoption, business evolution, market support and creation, and management uplift for the middle tier of high growth, higher potential productivity firms. This is where better regional economies come from- a better everyday economy - and it’s where the UK struggles most. The main issue when it comes to productivity is the top-middle tier of businesses not the top ten percent or that long tail.

Overall though, this Budget was an economic intervention of a developmental state. And given the failures of recent economic governance attempts, Thatcherism on steroids, muddle through, and austerity Britain, this strategy is a relief. As stated previously, it should at the very least deliver better infrastructure, growth potential, public services and green transition albeit with higher debts and possibly slightly higher interest rates.

Is a developmental state enough?

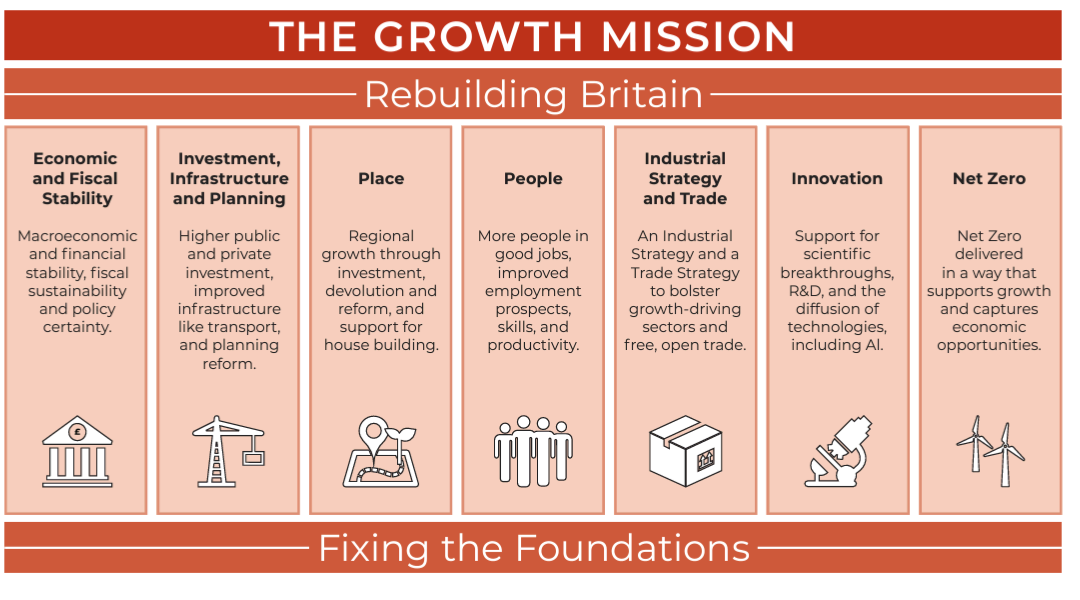

There are two big drawbacks to a developmental state as every single version of it has found: firstly, you run out of catch-up space after a time and that creates all sorts of financial imbalances; and, secondly, they are better for pursuing growth than other objectives. In fact, there was a handy growth mission chart included in the Budget, which, given this is Whitehall, was arranged into pillars, each broadly sitting with a Government Department.

These are all essential pillars for a developmental state. The “place” and “people” dimensions need a lot more elaboration and we will see that as local Government reorganisation comes into scope in the English Devolution Bill, local growth plans take shape and Skills England gathers pace. I do wonder if the “people” pillar gets sufficient attention. £300m extra for FE in the Budget is welcome but there is still a huge public and private investment gap in skills- put simply, employers and individuals don’t invest enough. If the developmental state is to succeed it will need workers with agile skills, innovators and investors, managers and technicians all with strong skills and institutional supports. The Spending Review will need to circle back on the “place” and “people” dimensions.

There’s something else more fundamental and will need a wider lens. The Government has not only a growth mission but health, environment and opportunity missions too - all underpinned by a commitment to fairness. This latter commitment is seen in the Employment Bill and increases to the National Living Wage. Priorities are answered in trade-off questions. Should we increase fuel duty or hold off on increasing the cost of living? Should we concentrate resources on small or high growth businesses? Should we invest in entry or higher level skills? How you answer depends on your priorities. The language of priorities is the religion of socialism as Nye Bevan would remind us.

The risk of developmental state is that wider objectives, while present, get frequently pushed aside if they make growth more complex or challenging. A growth mission that more explicitly draws in health, the environment (beyond delivering Net Zero as a strategy for growth), and fairness (for “people” and “places”) would be a real paradigm shift. It would need a strategy of sustainable production and consumption. In other words, a determination not just to see increased output but new business models, new ways of measuring business performance beyond financial measures alone, to see positive social and environmental innovation alongside business innovation.

All of this would require a different way of state institutions co-innovating at local, regional and national level with business and public services. This innovation would foster growth in itself as it means the development of innovative new business models. There’s a great example of the potential for co-innovation in the Budget with funding put aside for bringing together health, skills and employment support in eight regional trailblazers. If the Government is going to fulfil the promise of all its missions then health, opportunity and the environmental missions need to be integrated into the growth mission. The best way of avoiding trade-off questions is acting up-front to prevent them from emerging.

Cultivating the next economic paradigm

In so many ways this Budget opened out genuinely new possibilities. There are risks lurking in the gilt markets, in the behavioural responses to tax changes including on wealth, whether the British state can deliver on the opportunities and in private investment not following through despite the strong signals to invest. Nonetheless, the context is an extremely challenging one post-Brexit, post-governing failures. And given that, the Chancellor has played a weak hand well. As a matter of priority, it is better to deploy familiar strategies at an early stage and this departure from orthodoxy has plenty of space to evolve. For what it’s worth, I sense that the Chancellor has judged the risks and opportunities well.

To get into a transformative space, one that is implied by the Government’s missions, will require a further shift in statecraft and governance throughout the lifetime of this Parliament. There are few off-the-shelf examples for this mission so an innovative new statecraft will be required. Who said governing was easy?

Next I will return to the “three economies” and how they are co-dependent and what this might mean for policy and institutions. I promised that this week but, well, there was a Budget and it was a significant one.